‘My friend just gave birth to a baby with Down’s Syndrome. How can I help?

By Chaya Ben-Baruch, co-founder, Neshikha.com

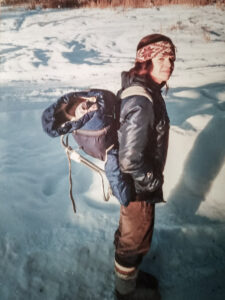

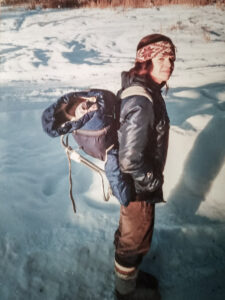

Chaya and Avichai, circa 1991, in Fairbanks, AL.

When you find out that your friend just gave birth to a baby who experiences Downs, she may have already known that she was carrying a special child, or maybe it came as a total surprise; each parent may be at different stages of denial or concern, or, conversely, acceptance and joy.

Prior to giving birth to our son, Avihai, thirty years ago, an alpha-fetoprotein test and an ultrasound showed everything as “normal.” Since then, I joke that my reference to “normal” is only a dial on my washing machine.

Blessedly, a week passed before it was determined that my baby had an extra 21st chromosome in each of his cells. I had given birth to Avihai, my fifth child, after two consecutive miscarriages so I was already familiar with the feelings of grief and sadness after losing a potential baby.

I did not pray for health or an easy birth. My only prayer during the pregnancy was for a “live baby.”

Miraculously, our son’s heart condition did not manifest for a week, a week of reprieve to bond with our baby. We later understood that he would require open-heart surgery, and most likely had Downs. I have a son whom I carried through pregnancy with hopes that he would become the best that he could be; a genetic condition was not among my expectations.

Each parent accepts their differently-abled child in their own way. I worried that our son would not be accepted by others. I grew up in a time when children who were developmentally or mentally challenged were often institutionalized as standard practice. My mother never told anyone he had Downs because If he did not make it through open-heart surgery, she would not have to tell anyone about the genetic issue.

One of my closest friends offered much-needed support when she took a look at him and noted how cute he was and that he looked like one of my other children.

We sought out other parents with children who experience Downs. We read books and went to conferences hundreds of miles from our home to learn more and share experiences, successes, and disappointments, with other parents and siblings sharing the same new reality.

Our pediatric cardiologist came up to our city, Fairbanks, in the north of Alaska, once a month. When he first checked Avihai, he commented that he was pleased with how well he was doing given that the infant had holes in the upper and lower chambers of his heart and his mitral valve was dysfunctional. That one sentence of encouragement started the tiny roots of hope in my heart. Maybe my child would make it. Finally, someone spoke to us in a more positive manner, instead of offering only gloom and doom. In all the chaos, fear, and darkness, I needed to reach a glimmer of light. I spoke to seven other parents whose children also underwent open-heart surgery and that helped, too.

Most of my closest friends through this journey have been parents of special-needs children, and everyone’s outlook in life and dealing with the related issues vary; what might help one parent may not help others. I did not need a list of everything that could go wrong; I was dealing with a baby needing open-heart surgery – an unfeasible procedure in Alaska at the time. When Avichi was three months old, we two traveled to Portland Oregon, while my husband stayed in Alaska with our other children. A tsunami called “open-heart surgery” was headed my way and I was just in survival mode.

From speaking with other parents the best advice from them includes:

1) Don’t Say: “God only gives you what you can handle.”

Parents may not always know what they can handle. Do remind them they are strong and have handled other difficult situations. There will be many unknowns and the future may be uncertain. They may need to handle just getting through the next day, hour or second. Remind them that they will cope, and, hopefully, go beyond coping.

2) Don’t say: “I am sorry,” but rather, “I am at a loss of what to say.” As a parent you want people to accept your child, not to pity you, them, or feel sorry on your behalf they were born. Birth should be a celebration, not a .

Don’t say: “I will pray for your child.” Down Syndrome is not an illness, nor is it reversible, last time I checked. You can’t “get over it.” There are even countries that are trying to “eradicate” Downs – as if it was a disease like polio, but their brutal, eliminationist method is to prevent any child with Downs from being born in the first place by strongly counseling expectant mothers to abort the fetus.

Life is often a chaotic balance of passionately joyous, and, supremely trying, situations; in Hebrew, we use the term “Tikkun” – a spiritual rectification or repair – to encompass how we respond to these challenges. In our case, Avichai’s birth proved to be a catalyst to spur our internal growth and fortitude. We used to be “handicapped-tolerant.” Now we’re “handicapped-involved,” and helping special-needs children to survive and thrive has become my enduring passion.

Having a baby with any genetic or birthing difficulty can be bittersweet, but the growth parents experience in accepting difficulties can change them in positive ways they never anticipated. But don’t be too optimistic at first; the parents may be grieving the “perfect” baby they did not have. Link them up with other parents who have been through such events.

The late Rabbi Noah Weinberger was the founder of the renowned “Aish Hatorah” religious seminary, located in Jerusalem’s Old City. When one of his married students told him that his wife had just given birth to a child with Downs, he broke down and admitted that he was not sure if he could cope with raising a Down’s child, Weinberg compassionately replied that “…only this child has the ability to open a place in your heart that no one else can.” I find this to be true, and I find it something I often tell Downs parents, of how only this child can love you in a way no other could. Later – sometimes weeks, sometimes months – those reassured parents have contacted me to share how those words buoyed them through rough times.

Avichai Ben-Baruch at arts and crafts, circa 1994. (Photo: Chaya Ben-Baruch

If you want to help a friend who has given birth to a Downs child, tell her how cute their child is. Ask to take pictures of her baby, and share them with her. Mention how the baby (Name) looks like his or her other siblings or grandfather. Call the child by name. If you can, pick up and cuddle and talk to the baby, and welcome him or her into the world. If you see the baby has improved over time, let the parents know, like sharing that “She looks better than last week;” “Hey – she’s gained some weight” – kids with Downs don’t usually gain weight easily, and later. as adults, often struggle to keep their weight nominal for their age and build.

In any case, don’t avoid your friend; do the things you may have done had the baby been non-Downs. Even saying something awkward due to unfamiliarity with dealing with Downs infants and children, when said by a loving friend, is easily forgiven. You can ask how your friend or her family are dealing with the diagnosis.

If the baby does not have any pressing medical issues or after they have undergone surgery and are then relatively stable, consider babysitting, even for a short time. Remember: a baby with Downs is first and foremost like most babies. As you get more used to the baby you will understand that and see them as kids with great smiles that usually are pretty happy.

You may find that your investment pays off. Many kids who experience Downs touch their world in a special way. You may find that your friend’s baby becomes one of your most favorite people.